As a bedside nurse, part of my job is to perform patient/family education. It is honestly one of the things I love to do. Since I’m in the NICU, I do most of my teaching to parents and families instead of to my neonatal patients. I can teach parents about how to care for their baby with lessons on feeding, diapering, or bathing, but I can also reinforce their understanding of their child’s diagnosis or medical condition.

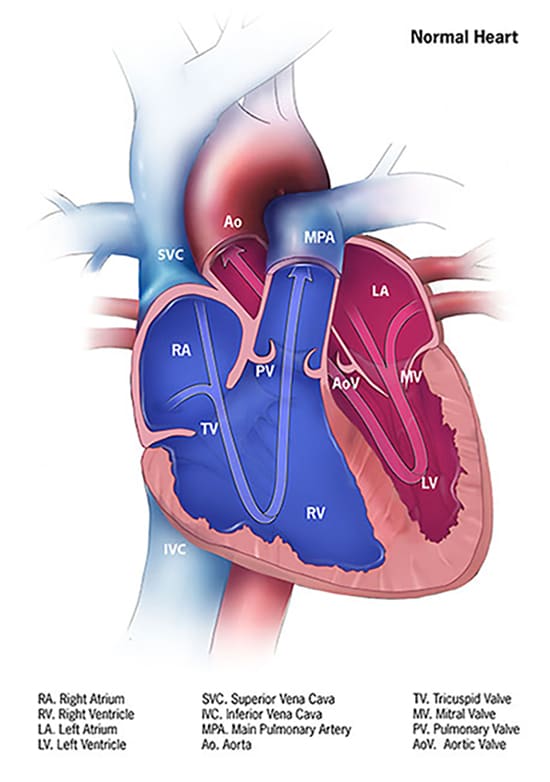

At my Level IV NICU, we tend to see a lot of cardiac patients and babies born with congenital heart defects (CHD). Some of these conditions are rare and not easy to understand; even more difficult to understand without knowledge of how a normal heart works. Personally, I never knew or understood blood flow through the heart until I took anatomy and physiology. Not all our parents or caregivers have had anatomy and physiology. So how do I explain what’s going on with their baby?

There are reputable websites I can refer to that have pictures to better understand CHD – I think they’re great for healthcare professionals and nursing students as well. One of them is the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/heartdefects/index.html.

Another website that’s a great resource for CHDs is Cincinnati Children’s https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/service/c/cardiothoracic-surgery. Cincinnati Children’s even offers animated heart videos to illustrate various heart conditions. While I love and recommend these resources, I’ve been wondering how I could further simplify patient teaching. In nursing school, I was taught to conduct patient teachings at the 5th grade level. Healthcare professionals should simplify teaching to their patients and patients’ families and use words such that a 5th grader could understand.

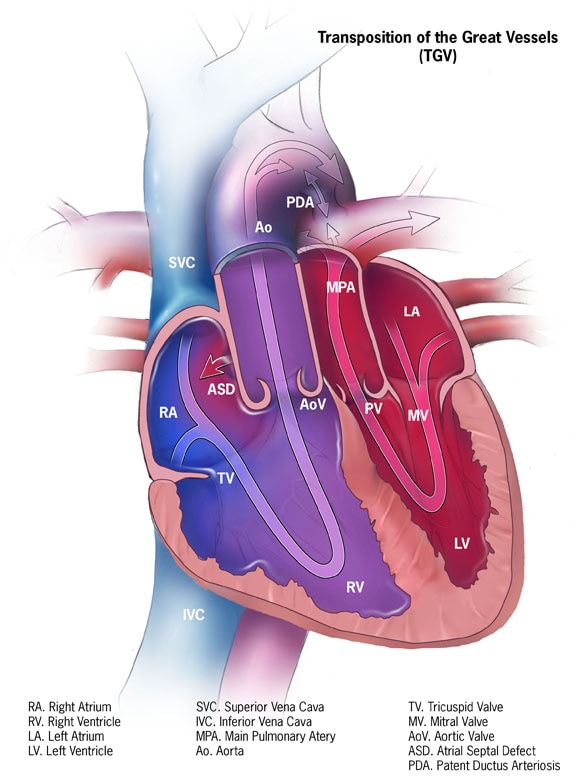

Recently, I’ve been thinking about teaching for a family who had a baby come to our hospital with a rare congenital heart defect, Transposition of the Great Arteries (TGA, or d-TGA). They seemed hesitant in explaining their child’s condition. They held up their hands and shared their baby’s arteries need to be like this (as they held their hands up, crossed like an ‘X’) but that their baby’s arteries are like this (as they held their hands parallel) to each other. They were not wrong in their explanation, but I wondered if they understood why it needed to be “crossed”. I felt like a process diagram could have been helpful.

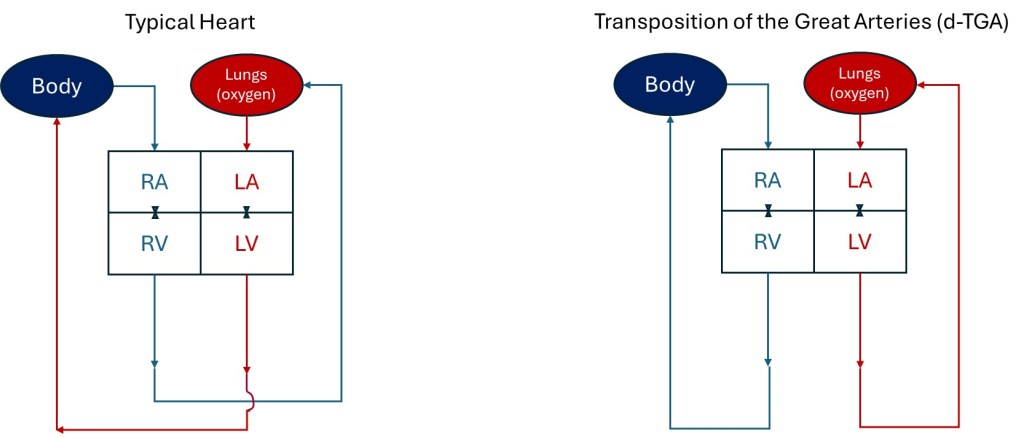

As a former engineer, I used to make flow charts in either designing or explaining existing manufacturing processes. I really wanted to simplify the explanation of blood flow to /from the heart with a process diagram. I drew it out when I got home and then tried to replicate what I drew on the computer. Below are the process flow diagrams I designed, using the same abbreviations as the CDC used to describe parts of the heart in their diagrams: RA = right atrium, LA = left atrium, LV = left ventricle, RV = right ventricle. I also used red to represent oxygenated blood and blue to represent oxygen depleted blood. I represent the tricuspid and mitral valves with the valve graphics used in engineering diagrams. I drew the little curve on the Typical Heart drawing to show the vessels leaving the heart don’t intersect/mix as they cross one another.

It’s not an accurate anatomic representation with size and doesn’t depict all the ways the blood enters the heart or how the arteries go up and out of the heart. The vessels and all the valves aren’t even labeled, but I think it easily shows why TGA is such a critical heart defect. From my flow diagram, I think it’s clear the rest of the body can’t receive oxygen with d-TGA because blood from the lungs can’t be delivered to the rest of the body. As a healthcare professional or nursing student, I love the CDC and Cincinnati Children’s images to explain the heart and defects. However, as an engineer, I love the simplicity of my flow diagrams.

If you were a 5th grader, what graphics are easier to understand? What do you think about my depictions? For my next blog post, I’ll share the diagrams I made that show how a baby survives d-TGA until they receive surgery to switch the arteries and correct the flow to the lungs and body. Hint: Look at the ASD and PDA in the CDC graphic for the TGV heart.